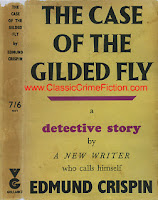

THE CASE OF THE GILDED FLY is the book that introduced the world to Gervase Fen, the eccentric Oxford don, specialist in English Literature and Language and extraordinary murder mystery solver. Because I'd read THE MOVING TOYSHOP (another Fen adventure) last year and loved it, my friend John from PRETTY SINISTER BOOKS, generously sent me a copy of GILDED FLY and that's how I wound up reading it for the first time.

We arrive in 1940 Oxford by train with the whole cast of characters in various compartments including Fen. So we're introduced right away to the dramatis personae (including the killer, of course) who will play major roles in the upcoming mystery: two of them (three if you count the killer) will meet with grisly ends. But let's not get ahead of ourselves.

Also traveling on board the train is Nigel Blake, a friend of Fen and eager to see him again. (They each don't know they're on the same train.) Blake is a poet given to quoting obscure English poets in moments of stress and even otherwise. He is vaguely a Watson to Gervase Fen's Holmes if you want to pigeon-hole his role in the story.

The assorted characters we meet early on are almost all members of an acting troupe which will be putting on famed playwright Robert Warner's new play at the Oxford Repertory Theater. They have a week to set the thing up and give the play it's highly anticipated premiere.

The book's action takes place during that week at the actors' Oxford digs (primarily the Mace and Sceptre, a hotel in the center of town) and in the theater where the play is being ground into shape. Nigel Blake is invited along to watch and he is thrilled to do so since he has a crush on one of the actresses, Helen Haskell, though he's never met her.

There is is much emotional give and take among the actors, cast and crew, the usual love affairs and intrigues, gossip, likes and dislikes. The usual familiarity among groups of this sort. The most disliked member of the troupe is a young woman by the improbable name of Yseut Haskell.

Yseut is the made to order victim, seeing as no one has a kind word to say about her. She is the sort of femme fatale whose charms may have seen their better days even if she is still young enough and sexy enough to cause dissension in the ranks. A red-headed trouble maker par excellence, given to malice and excessive drinking to boot.

So when Yseut is murdered there's no display of grief, even from her half-sister Helen. In fact, cast and crew are nothing if not rather cold-bloodily relieved that she's out of the way and now they can concentrate on putting on the play.

Gervase Fen and his friend Nigel are practically on the scene when Yseut is found shot to death at the Mace and Sceptre. It's kind of a locked room puzzle, though the room was not locked merely under keen observation since everyone seemed to be hanging around while a murder was committed under their very noses. Not surprisingly Fen claims he knows the killer right off the bat. But for purposes of keeping the plot moving right along, Fen doesn't reveal the news. His reticence to do so causes another person to be foully murdered. But, oh well, nobody's perfect.

While this book doesn't have the same out of hand exuberance that made THE MOVING TOYSHOP such a joy to read, it is still an entertaining mystery and whats more we get to meet Gervase Fen's patient and understanding wife and learn that he does, in fact, have some kiddies waiting at home. Who knew? These species of crime solvers are usually confirmed bachelors so Fen's family life came as a surprise to me. I don't remember it being mentioned at all in the previous book.

This particular Oxford Don's idiosyncrasies are spelled out clearly and he brilliantly lives up to the word, 'eccentric'. After all, where would our mysteries be if they didn't have an eccentric or two involved in the solving of them? I wouldn't like these books half as much without a character such as Fen to muddy the waters and make me yank out my hair with frustration - I exaggerate, but you know what I mean.

Nigel reflected, as he turned into St. Christopher's at twenty to six that evening, that there was something extraordinarily school-boyish about Gervase Fen. Cherubic, naive, volatile, and entirely delightful, he wandered the earth taking a genuine interest in things and people unfamiliar, while maintaining a proper sense of authority in connection with his own subject. On literature his comments were acute, penetrating, and extremely sophisticated; on any other topic he invariably pretended complete ignorance and an anxious willingness to be instructed, though it generally came out eventually that he knew more about it than his interlocutor, for his reading, in the forty-two years since his first appearance on this planet, had been systematic and enormous.

If this ingenuousness had been affectation, or merely arrested development, it would have been simply irritating; but it was perfectly sincere, and derived from the genuine intellectual humility of a man who has read much and in so doing has been able to contemplate the enormous spaces of knowledge which must inevitably lie beyond his reach.

In temperament he was incurably romantic, though he ordered his life in a rigidly reasonable way. To men and affairs, his attitude was neither cynical nor optimistic, but one of never-failing fascination. This resulted in a sort of unconscious amoralism, since he was always so interested in what people were doing, and why they were doing it, that it never occurred to him to assess the morality of their actions. The fuss about what he shall do in connection with Yseut's murder thought Nigel, is entirely characteristic.

It is this characteristic, never the less, which results in a second murder which might have been averted. So it's kind of hard to reconcile the word 'delightful' with Fen's actions in this particular case.

One thing I could have done without: chapter headings which feature tidbits of obscure English poetry mostly in the original olde English. I mean, they make you feel like a dunce if you don't know what on earth they refer to - which I mostly didn't. Was this a kind of supercilious hostility on the part of the author? Maybe not. Maybe in the early fifties people did know all this esoteric stuff and could quote these things at the drop of a hat. I wouldn't be at all surprised.

I also have a quibble with the grand denouement which comes after a brilliant opening night performance of the play, and it is this: not only is the 'how-to' explanation far-fetched, but the motive comes out of left field, a 'huh?' moment when it is finally revealed. I don't know about you, but I'd like a really good motive for a crime as nasty as double murder, especially when one of the murders involves an ugly throat cutting.

And the 'gilded fly' in the title is kind of a tacked on thing which makes little satisfying sense.

These Golden Agers of the Locked Room School are mostly stories told with wit and humor that take great pleasure in convoluted methods of murder and confusing the heck out of the reader. They are more intellectual puzzles than out-and-out satisfying whodunits. In that, THE CASE OF THE GILDED FLY succeeds admirably. It is a grand first (in my case, second) impression for a series with which I hope to make myself more acquainted as time goes by.

This is another entry in my year long participation in Bev's VINTAGE MYSTERY READING CHALLENGE being hosted at her blog, MY READER'S BLOCK. Check in to see who else is reading what vintage and expand your ever-growing TBR list.

Yvette: I don't think Crispin meant to be looking down his nose with those quotations. I take it in the same way I take Dorothy L Sayers sprinkling all sorts of literary references and Latin and French throughout her Wimsey novels...to her it was natural that educated folk would know all that stuff.

ReplyDeleteBev: I think possibly with Sayers writing earlier, that WAS the case. People then were much more versed in the classics. And possibly even in the early fifties, though I don't remember it as such. But then how would I? I wasn't growing up in Oxford. :)

ReplyDeleteWhy do I laugh so hard when I read these book reviews? They are so funny.

ReplyDeleteI kind of lost track in a few of the very long sentences, but I laughed anyway, as the language is very funny.

Locked-room mysteries are fun. Even the one by Sjowall and Wahloo had an incredibly complicated solution. They must have discussed (and tried it) for days -- I mean, tried the logistics of how it worked.

These sound great. I love British mysteries. I hate obscure quotes that make you feel stupid. What is that about?

ReplyDeleteI need to stop reading your reviews as they end up making me pick up even more books. I'm still not sure I forgive you for my current Mary Roberts Rinehart obsession.

ReplyDeleteI picked two more of her books last week.

Kathy: They're fun, but they must be kept lively or they can become tedious. While not as much fun as THE MOVING TOYSHOP, this one was lively enough.

ReplyDeleteRobyn: This is a very typical sort of British mystery. It actually reads as if it were written in the thirties. It has that fun vibe to it.

ReplyDeleteOh well, I just ignored the obscure quotes since I couldn't make heads or tails of 'em. :)

Ryan: First Kathy gets obsessed with Nero Wolfe and now you're obsessed with Mary Roberts Rinehart. I am the Queen of Turning People into Reading Zombies!! Ha!

ReplyDeleteKidding aside, I'm glad you're enjoying my reviews, Ryan. Truly.

Even if they make you run out and buy more books.

Yvette, I'm glad you're enjoying Crispin. If it makes you feel any better, I also miss most of the quotes - and I was an English major! Of course, that was back in prehistoric days... ;-)

ReplyDeleteLes: I'm glad to know I'm not the only one. Ha! Yes, I'm enjoying Crispin's world.

ReplyDeleteExcuse me -- not reading zombies, reading sloths. Fully alive, but prone and moving slowly (especially in the heat).

ReplyDeleteTalking of obsessions, I just read the introduction to Champagne for One and it's by none other than the late, great Lena Horne.

She loved Nero Wolfe books, took them with her on tour and read them when she missed New York. She loved Archie.

Also, she knew Rex Stout. Their children were in the same school. She visited him and -- guess what? His house was full of orchids everywhere, just like the West 35th St. brownstone.

One can never guess at who likes which authors? Who would have thought of Lena Horne as a fan of Archie and the gang's?

Kathy: I know! I was so intrigued by this bit of news when I first read it a while back. I think Lena Horne mentions that her husband and Stout were also great friends. I loved reading about Stout's house filled with orchids, too.

ReplyDeleteAnd by the way, what kind of name is Yseut? Just reading that made me laugh. Perfect for an annoying murder victim.

ReplyDeleteI have to track this down.

I looked up Yseut. It's related to Isolde, of opera fame, and to Iseult. Also a variable on it is -- you guessed it -- Yvette.

ReplyDeleteKathy: No kidding! Thanks for that bit of news, Kathy. :) I'm assuming the name is pronounced EE-SAU. You think? I do.

ReplyDeleteVery exotic.

I think they mention Tristan and Iolde in the book, but you know my memory...!