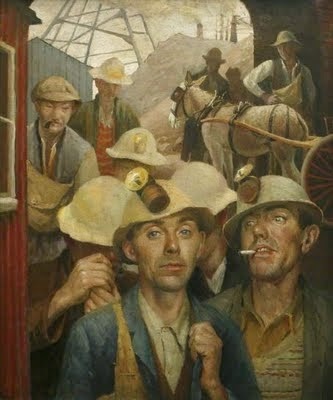

'Summer in Cumberland ' - British painter James Durden (1903 - 1993)

In between vintage mysteries as they arrive on my doorstep or on my new Kindle, I've discovered the delights of the very elegant British writer Angela Thirkell (1890 - 1961). Though Thirkell is considered by some as a 'minor' writer, in my view, she has the slyness and grasp of language of a Jane Austen had Austen lived and written in more modern times. (I must say that Thirkell often makes me laugh out loud and Austen, though very wise, makes me smile and shake my head in recognition but rarely makes me scare the dog with jollified outbursts.)

Thirkell's books are the sort of thing in which nothing much happens except the major and minor exigencies of day to day life, but still, you can't stop reading. Most of her books are set in the fictional county of Barsetshire (much earlier created by the 19th century author, Anthony Trollope) and the stories are all about the countrified life of the British upper classes before, during and after WWII. Every relevant and not-so-relevant thing is seen through a slightly jaundiced eye and described with the author's decidedly wicked wit and most of the books end in the happy embracement of a fortuitous marriage or, at the very least, a providential engagement or two.

At this stage of life, a battered old cynic (like me) really does value a happy ending here and there. But I love it when there is no attendant goopiness to gum up the works - Thirkell eschews goopiness. Her style may hide a hint of cold glitter beneath the surface, but it's up to the reader, I think, to decide just how much of it to unearth.

Thirkell's keen enthusiasm for a Britain that is no more and her casual indulgence of the eccentricities of the British upper (and lower) classes doesn't negate the occasional pointlessness of it. It is pertinent to remember, though, that these are among the sorts of people who kept German bombers at bay in the early part of WWII, did their duty, lived and died and loved their king and country.

A small bit of author bio: Angela Thirkell was the granddaughter of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, daughter of a Scottish Classical Scholar and Oxford Professor of Poetry and through her mother (daughter of the painter) was also distantly related to Rudyard Kipling and P.M. Stanley Baldwin - according to Wikipedia.

Though some would suppose you ought to read the Barsetshire books in order, I haven't, and yet I'm enjoying every moment spent among the sorts of people whom I very much enjoy encountering in fiction. Such is Angela Thirkell's brilliant finesse that all snobbery is forgotten and forgiven. And the charm, oh the wonderful British charm - maybe in place to make up for the usually odious English summer weather which necessitates the warmth of blazing fireplaces in July and the fortification of copious cups of afternoon tea. But even on those rare occasions when the sun shines, tea and scones are never far away.

I've read nine of Thirkell's Barsetshire books so far, and can only think I found them at just the right time in my life.

Now rather than talk about any one specific book, I'll just quote (at length) from a favorite, AUGUST FOLLY (but Yvette, isn't that the same thing?), which will I hope, give you some idea of Thirkell's style, wit and charm.

I'm also including a link to a comprehensive list all of Angela Thirkell's books and also a page of book summaries, both provided by The Angela Thirkell Society of North America, a terrific place to go to find out more about Thirkell and her work.

"The little village of Worsted, some sixty miles west of London, is still, owing to the very defective railway system which hardly attempts to serve it, to a great extent unspoilt. To reach it you must change at Winter Overcotes where two railway lines cross.

Alighting from the London train on the high level, you go down a dank flight of steps to the low level. Heavy luggage and merchandise are transferred from the high to the low level by being hurled or rolled down the steps. From time to time a package breaks loose, goes too far, and trundles over the edge of the platform on to the line, but there is usually a porter about to climb down and collect it.

When your train comes backwards into the station, often assisted for the last few yards by a large grey horse and its friends and hangers-on, you may take your seat in a carriage which has never known the hand of change since it left the railways shops in 1887. If it is market day at Winter Overcotes your carriage will gradually fill with elderly women, carrying bags and baskets, who prefer the train to the more expensive motor-bus, children with season tickets coming back from school, and one or two old men who still wear a fringe of whisker...

...The line meanders, in the way that makes an old railway so much more romantic than a new motor highway, among meadows, between hills, over level crossings. At Winter Underclose, Lambton and Fleece, the train stops to allow the passengers to extricate themselves and their baskets from its narrow doors. It then crosses the little river Woolram and enters a wide valley, the further end of which is apparently blocked by a hill.

Just under the hill is Worsted, where you get out. The valley is not really impassable, for a few hundred yards beyond the station the train enters the famous Worsted tunnel, whose brutal and unsolved murders have been the pride of the district since 1892.

The line is staffed and controlled by three local dynasties; Margetts, Pattens and Polletts. If a Margett is station-master, you may be sure that there is a Patten in the goods yard, or on the platform. If a Patten is engine-driver, his fireman can hardly avoid being a Pollett. If there is a Pollett in the signal-box, there will be a Margett to open the gates of the level crossing and warn the signalman that a train is coming. All three families are deeply intermarried.

Mr. Patten is the station-master at Worsted. His head porter is Bert Margett, son of Mr. Margett the builder, and his nephew, Ed Pollett, whose father keeps the village shop, is in the lamp-room, and gives such extra help as zeal, unsupported by intellect, can afford. He also has a genius for handling cars.

The inconvenience of the hours of running is made up for by the kindness of the staff. They will hold up a train for any reasonable length of time if old Bill Patten, cousin of the station-master and father of the second gardener at the Manor House, is seen tottering towards the station half a mile away; or young Alf Margett, Bert's younger brother, from the shop, has forgotten one of the parcels he should have brought on his handlebars, and has to go back to fetch it. Since no trains can proceed until their various drivers have exchanged uncouth tokens of metal, like pot-hooks and hangers, or gigantic nose and ear-rings to be bartered with savage tribes for diamonds and gold, there is no danger.

Most of the land hereabouts is owned by Mr. Palmer, whose property, bounded on the north by the Woolram, runs south nearly as far as Skeyne, the next station down the line. East and west are Penfold and Skeynes Agnes, where there is a fine Saxon church. Mr. Palmer is a J.P., an excellent landlord, and owner of a very fine herd of cows which supply Grade A milk, at prices fixed by the Milk Marketing Board. His wife, in virtue of her husband's position and her own masterful personality, has taken the position of female Squire.

Of other gentry there are few in the immediate neighbourhood. Lady Bond at Staple Park does not count, because she and Mrs. Palmer have not for some time been on speaking terms. There are also the Tebbens, who live at Lamb's Piece, near the wood above the railway.

At the moment when our story opens, on a warm June morning last summer, Mrs. Tebbens was in her drawing-room, reviewing a book on economics. Happening to raise her eyes to the window, she saw Mrs. Palmer opening the garden gate, so she went to warn her husband."

AUGUST FOLLY, 1936 - by Angela Thirkell

Once I'd read this far, resting comfortably in bed, snuggled under the covers with Rocky at my side, I had no choice but to stay up all that night and read the rest of the book, occasionally laughing out loud and enjoying myself enormously.

I suppose you have to have a bent for this sort of deliciously meandering writing to enjoy it as much as I do, but for those of us who do, Angela Thirkell's books are a gold mine. Put everything aside and go find some.

Need more convincing? Link to this 2008 Angela Thirkell opinion piece by Verlyn Klinkenborg in the NY Times.

P.S. And yes, I am bound to begin reading Anthony Trollope this year.

'On the Balcony' by James Durden. Another painting I think shows the Thirkell style.

%2BHarold%2BLehman%2C%2BAmerican%2C%2B1913%2B-%2B2006.jpg)