Pages

▼

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

What would HItchcock make of this? What would Tippi Hedren?

THE BIRDS is one of those movies that always manages to draw you in and keep you glued to your seat, no matter how many times you've seen it. At least it does, me. Hop on over to iluvcinema's blog and check out the overview of one of Hitchcock's most intriguing films.

After you're done giggling here, that is.

When I saw the (somewhat strange) Madame Alexander doll (see above), I had to post the pix in the spirit of my adding THE BIRDS to my Netflix queue. Isn't it a hoot? It's been too long since I've seen nature run amok in Bodega Bay.

I found the doll pix at this link.

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

Tuesday's Overlooked (or Forgotten) Films: ANGELS AND INSECTS (1995) starring Mark Rylance and Kristin Scott Thomas

It's Tuesday, so it's Overlooked (or Forgotten) Films day again, hosted by Todd Mason at his blog, SWEET FREEDOM. Don't forget to use the link and catch up on what other overlooked films other bloggers are talking about today.

**************************

ANGELS AND INSECTS, directed by Philip Haas, is a difficult film to speak of without giving the shocking denouement away. There's a huge build-up towards that moment and the viewer probably sees what's going on before the hero, naturalist William Adamson (played brilliantly by the wonderful Shakespearean actor, Mark Rylance), so I'm not sure how shocking it really is.....yeah, it's shocking. Prepare yourself.

This is a beautifully opulent movie about very ugly notions. Actually, it's one of the most beautiful movies I've ever seen, despite the loony-toony underpinnings. How can that be? You'll have to make up your own mind. The time is the late 1800's and ANGLES AND INSECTS has the many lush romantic overtones the Victorians loved, as well as the darkly Gothic inclinations of their literature.

Whenever I think of this movie, I tamp down the unpleasantness and think only of the enormous amount of production detail that went into filming A.S. Byatt's original story. It is this attention to detail which enriches what would otherwise have been just another sordid (perhaps more sordid than most) story highlighting Victorian hypocrisy and love run amok.

Victorian England knew a great deal about sordidness, but it was kept well hidden behind the facade of social respectability and good manners, not to mention, proper clothing. Willful and intentional blindness did a lot to keep these fine young ladies and gentlemen playing at perfection under the benevolent reign of a rigidly inclined queen.

The film's cinematography by Howard Zitzermann (the butterfly scene alone is worth the price of admission) is brilliant, as are the dazzling (and I mean, dazzling) costumes by the incredibly talented Paul Brown. I'd venture to say that the movie is worth seeing just for the costumes alone, if you're so inclined. Sometimes visual artistry in a film is lure enough.

Adamson is a naturalist a bit out of sorts with society's deceits, having just come back from a trip to the jungle wilds. In fact, you see him joining in some sort of native ceremony during the opening credits.

In truth, I suspect (and you will too) that Adamson has been brought to the house more for Alabaster's daughter's sake than anything else. He appears to be excellent husband material.

The daughter, Eugenia (Patsy Kensit) is a pale blond creature of icy exquisiteness and Victorian sensibilities - but she seems almost too frail, too delicate, too retiring - all, apparently, that a lady of a certain type should be.

One of the movies most memorable scenes - a scene which visually explains Miss Alabaster's personality - takes place in the house's conservatory. In order to charm Miss Alabaster, Adamson has released a multitude of butterflies at the moment of their emergence from various cocoons. He wants to delight Miss Alabaster with this exquisite combination of science and beauty.

She is delighted. At first.

As events in the house take on a day to day routine and Adamson becomes part of the scenery, we see that there is something moving beneath the calm surface, something not so nice, not so polite.

Well, we see it, but Adamson, unfortunately, doesn't.

Much of what is meant is rather obvious - a tale told by the costumes themselves.

Lady Alabaster (Annette Badland) as photographed, appears to be made of royal jelly herself, too fat to get around much, she's meant to be a hideous queen bee on her last legs. She is inclined to spells of the vapors, done up as she is in gowns and shawls and Victorian whatnot in the heat of the summer. Unhappy servants fetch and carry for her.

The children, some of them appear to be triplet girls, buzz around her dressed in gowns and costumes in colors resembling the variety of insect life which live on the grounds of the estate. I'm sure you'll notice the eye-popping yellow and black bee striped dress worn by Patsy Kensit in one scene.

An overwrought tea party out on the lawn.

As Adamson attempts naturalist lessons for the childrens' sake, he unearths plenty of insect life while Miss Matty (Kristin Scott Thomas) Lady Alabaster's companion, takes up a sketch pad. They have much in common, conversing while the family spends their time indulging their whims.

In fact, her talent for sketching is so ideal that Adamson encourages Mattie to work on a book. A naturalist bible, categorizing the variety of insect life to be found in the English countryside.

In fact, her talent for sketching is so ideal that Adamson encourages Mattie to work on a book. A naturalist bible, categorizing the variety of insect life to be found in the English countryside.

Kristin Scott Thomas and Mark Rylance

The camera makes sure to capture, in close-up, insects in different forms. At one point, one too many bees drive a tea party indoors. We are more or less forced to make the inevitable comparison - the sluggish activities of the house's human inhabitants to those of the busier, purposeful insects.

When Miss Alabaster charms Adamson into the expected proposal of marriage, she readily accepts. But you know something is not quite right at Casa Alabaster. The feeling is made clearer when you notice the odd interaction between family members.

The brother, Edgar Alabaster (Douglas Henshall) is nothing but a spiteful lout with obvious malice towards Adamson and a droit du seigneur attitude towards the servant girls.

The mother is fast fading away of some undisclosed condition, while the husband, Sir Harald, fusses about all day in his study/laboratory, ignoring the human drama outside his door. Perhaps already aware that a changing of the guard is underway.

Mark Rylance and Douglas Henshall (Edgar Adamson)

There is a great uneasiness lurking in the house. The servants apparently know, but keep quiet about it for fear of losing their positions. The only one who keeps an aloof eye open and may or may not speak is Miss Matty, the governess.

Over time, several children are born to Adamson and his wife, but he becomes restless - confined to living in one place. Though he loves his wife, he feels oppressed. The only one he can really talk to is Lady Alabaster's companion, she is the one person who speaks with him of the things that might actually interest a naturalist and man of science and ideas. Adamson finds himself contemplating the attractions of rational thought and artistic skill.

Kristin Scott Thomas and Mark Rylance studying nature.

When the full scope of what has been going on (I really can't say any more) is revealed, Miss Matty and William Adamson give us the only ending possible.

This is a definite R rated film, there is nudity and sexual activity, not to mention the repulsive doings that force William Adamson to - finally - acknowledge the truth in a harrowing, superbly acted scene near the end.

But if I can take it, so can you. In spite of everything, it's a hauntingly beautiful film though the story itself is as ugly as can be. Human beings can be a nasty lot. Insects, at least, don't bother pretending.

Saturday, February 25, 2012

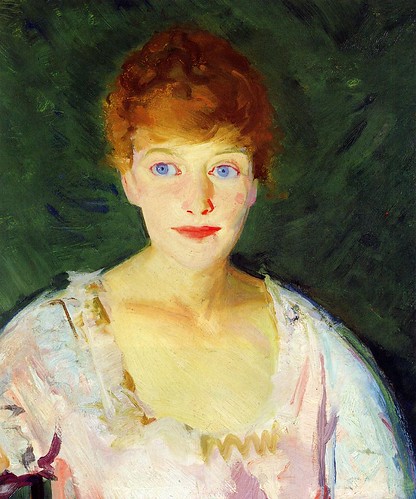

A Favorite Painting or Two.....or Three!

Edna Smith In A Japanese Wrap

Dutch Girl in White 1907

Spanish Girl of Segovia

The Little Dancer

Salome

The Laundress

'Pet' aka Wee Annie Lavelle

Carl Sprinchorn

Johnny Patton

Isolina Maldonado, Spanish Dancer

The Goat Herder aka Mexican Boy 1917

Lucie

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 1916

Robert Henri (1865 - 1929) was an American painter born (Robert Henry Cozad) in Cincinnati, Ohio. His father was a gambler and real estate developer who became embroiled in scandal out west and the family eventually worked their way east to New York and later Atlantic City, New Jersey, the children having changed their names.

In 1886, Henri enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia where he studied under a protege of Thomas Eakins.

In 1888 Impressionism claimed another convert when Henri traveled to Paris. He was eventually accepted at the Ecole Des Beaux Arts and traveled to Italy and Brittany as well.

Upon his return to Philadelphia in 1891, Robert Henri began the most influential role of his life, that of teacher.

From Wikipedia: In Philadelphia, Henri began to attract a group of followers who met in his studio to discuss art and culture, including several illustrators for the Philadelphia Press newspaper who would become known as the 'Philadelphia Four': William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn and John French Sloan.

The gatherings became known as the Charcoal Club, featuring life drawing and readings in the social philosophy of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Emile Zola and Henry David Thoreau. By 1895, Henri had come to reconsider Impressionism, calling it a "new academicism".

Note: I've featured both William Glackens and John Sloan on the Saturday Salon.

Robert Henri later taught at the New York School of Art in 1902 where his students included Joseph Stella, Edward Hopper and Rockwell Kent.

Henri reconstituted his approach to painting, calling the National Academy of Design, 'a cemetery of art.'

The art critic Robert Hughes said of his work, "He has given it urgency with slashing brush marks and strong tonal contrasts. He's learned from Winslow Homer, Edouard Manet and from the vulgarity of Franz Hals."

Henri was closely associated with a movement in art which would later come to be called the 'Ashcan School' - but the name would not be coined until 1934, after Henri's death.

Henri admired the anarchist Emma Goldman, publisher of Mother Jones. Goldman - who sat for him - called Henri 'an anarchist in his conception of art and its relation to life.'

Henri died from cancer in 1929 at the age of 64. He was honored by a memorial exhibition of his work in 1931 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Please use this link to read much more about Robert Henri's life and work. Additional information can also be found at this link.

Robert Henri - Self Portrait

Friday, February 24, 2012

Friday's Forgotten Book: THE SINGING SANDS (1953) by Josephine Tey

Today is Forgotten Book Friday - as usual - but my book also qualifies as an entry in Bev's Vintage Mysteries Reading Challenge. Funny how that works out.

THE SINGING SANDS is Josephine Tey's last book and while it has a highly unsatisfactory ending (in my view, at least) it is still one of the more elegantly written mysteries I've ever read. On that aspect alone I would highly recommend it, even if you're not familiar with Tey's policeman protagonist, Inspector Alan Grant of Scotland Yard.

I'm not sure quite how to describe this book since so much of it does not fit the regulation whodunit, but I'll do my best.

Alan Grant is off to Scotland to stay with friends and recuperate from a plague of nervous fatigue which has taken the form of claustrophobic panic - a kind of post traumatic stress. Though we're not told exactly why this has come to pass. His unfeeling boss isn't happy to see him go even for a short while, he wonders why Grant can't just shake the thing off.

While on the train, just before his station, Grant chances upon a dead body in a compartment - B7, to be exact. But Grant is on recuperative holiday, so, despite misgivings, he leaves the death scene in the hands of a conductor and the local police.

But Grant has taken a look at the face of the young man and been impressed by what he's seen. The dead man has the face of someone Grant would have liked to have known as a friend.

Grant is fairly knowledgeable about faces and types since he is, after all, a cop. The dead man intrigues him. Primarily because the face with the arched eyebrows has the look (even in death) of an adventurer. It is a poetic, intelligent face which continues to pop up in Grant's thoughts as he goes about his days spent with friends, fishing and trying to relax, trying to free himself from his damned claustrophobic debilitation.

By chance, Grant's picked up a memento of the death on the train - a newspaper which was lying in the dead man's compartment. Grant had tucked it under his arm and walked away with it - hardly without meaning to. Turns out the dead man had been scribbling lines of poetry on the pages of the paper. The very enigmatic lines mention 'the beasts that talk, the streams that stand, the stones that walk, the singing sands...'

When the police investigation deduces that the man, Charles Martin - apparently a Frenchman - was falling down drunk and died an accidental death, that is the end of the investigation. Especially when he is identified by the Martin family (through an old photo) as their missing son.

Except that Grant thinks the handwriting in the paper - in English - smacks of English schooling. It has the look and feel, to him, of the Englishman.

On this vague deduction and the feeling evoked by the scribbles of 'poetry', Grant begins his own, slowly evolving investigation, on his own time, in between the fishing and the trying to be a reasonably good guest to his caring friends. Friends, by the way, who have even invited a beautiful lady with a title (whom Grant is nearly smitten with, much to his chagrin) to stay for a few days.

An aside: One of the reasons the book's ending was so unsatisfactory to me, is that this character, Lady Kentallen is quite spirited and delightful company. She pops into the story midway, then is left behind and never mentioned again as Grant returns to London a week early. There is also a second character who pops in later in the book as well, an American named Tad Cullen who is searching for a missing friend NOT named Charles Martin. He too is a wonderful addition to the cast, a young pilot who will 'flesh' out the character of the dead man and make me mourn his lost and trusting friend.

But let's return to Scotland: Try as he might Grant can't shake the nagging feeling that the death of Charles Martin isn't settled at all. He'll get no thanks from headquarters for messing about with an open and shut case, but Grant is not easily diverted when he gets an idea into his head.

On a hunch, he takes a side-trip to the Hebrides, to Cladda, a fairly isolated windswept spot where legend has it, 'the singing sands' can be heard while walking the miles of deserted beaches. While there, Grant is made no wiser about the mystery of Charles Martin - no one's ever heard of him - but he manages to cure himself of what ails him through enthusiastic soul searching, long walks, and spirited philosophical talks with himself, adding his own poetic ramblings to the mix.

Grant is a cop, but he is also a multi-faceted, humane man. The isolation and the stark beauty of Cladda nourishes him, refreshes his spirit and sends him back down to his friends a relatively 'new' man.

There is much going on in this story, besides a murder mystery. Josephine Tey has also given us a tale of self-discovery, adventure, lost cities in the desert, friendship and loyalty and the unrelenting search for truth.

What really happened to the man in the train with the English schoolboy handwriting and the face of a poet?

Eventually, with the help of Tad Cullen, the roots of an insidious murder plot are revealed and as vile a murderer as you will ever read about, is uncloaked.

To read this book is to take a journey inside Alan Grant's heart and soul, to selfishly wish, in the end, that Tey hadn't died soon after, if only because we'd have liked much more of Grant's company AND his deliberate, rationalized sleuthing. A complex, amazing man, whose company I will miss.

Even if he decides, in the end, that marriage is not for him.

Thursday, February 23, 2012

The Oscar isn't the only award being handed out this week...

I'm running a little late on my acceptance and thankful acknowledgement of an award I received a few days ago from Lucy Nation over at her wonderful blog, TALES FROM THE FARAWAY TREE.

I'm thrilled when someone recognizes the work that goes into framing and forming the almost daily posting that goes one around here. Lately, I know, I've been dragging a bit behind in keeping things brisk, but I've decided that posting on a daily basis might not be ideal for me.

Dare I say it? It's just plain hard work trying to come up with something interesting, entertaining and enlightening day after day - and believe me that's what I've always tried to do.

So when Lucy - out of the blue - rewards my efforts with an award, I am as thankful as can be.

Versatile - exactly what I try my damndest to be.

Thank you, Lucy.

Now I'm supposed to post 7 random things about myself that you might not be aware of....Hmmm, this might take a little bit of time. 7 Things...7 things.....7 things.......!

Ernie Bushmiller

2) We didn't have television at home until I was around 10 years old - and at that, we were only the second family on our block to have one. It was an Admiral (made in America) and it was nearly indestructible. It lasted many years. The first show I ever saw on TV was 'Rootie-Kazootie'.

3) I had a crush on Hercule Poirot when I first began reading Agatha Christie books back in my teens. Yes, it's true. To this day I adore the man. My only excuse is that I was always a big admirer of brain-power. I also loved his French...uh, Belgian, accent.

Of course, that was the Poirot of the books. Once I saw David Suchet's portrayal, I realized yet again that Poirot was the man of my dreams.

4) I am a Gemini. Which should explain things you may have wondered about.

5) At last it can be told: While I don't own a Gemini hat, I actually own a Deerstalker. You know, Sherlock Holmes and all that. I bought it in England, years ago.

Holmes is my second Big Crush, after Poirot.

6) If ever I should win the lottery, I'll be moving in across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

7) I still love picture books and a nice little collection. Why should kids have all the fun?

*****************************

I was supposed to name some new bloggers I thought worthy of receiving the Versatile Blogger Award, but after thinking about it, I've decided maybe it's better if I don't risk hurting anyone's feelings.(I've feeling chicken-hearted these days.) So I'm doing away with this part of my award duties.

Again, thank you Lucy, for thinking of me and most of all, for liking my blog.

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Happy Anniversary to The New Yorker Magazine...

The first New Yorker cover designed and drawn by Rae Irvin.

...which began publication on today's date in 1925. It remains, for me, the telltale arbiter of New York City literate life. This is not a magazine for 'the old lady in Dubuque,' as founder Harold Ross said, once upon a time.

But this old lady in New Jersey is very fond of Mr. Ross's creation.

Every year the magazine runs a contest where the public is invited to design their own anniversary cover featuring the top-hatted Eustace Tilley, a Regency dandy. who was drawn on the first cover by art director, Rae Irvin.

To see this year's winners, please use this link.

Overlooked (or Forgotten) Film Tuesday: MURDER SHE SAID (1961) starring Margaret Rutherford

Today it's Overlooked or Forgotten Films day ( as it is every Tuesday) at Todd Mason's blog, SWEET FREEDOM. Don't forget to check in and see what other films other movie mavens are talking about today. You're sure to find a film or two you'll want to renew acquaintance with or perhaps, view for the first time.

**********************************

I hadn't seen MURDER SHE SAID in many years and was thrilled when it became available on Netflix. This is the first and my favorite of the Margaret Rutherford/Miss Marple films which are very loosely based on the Agatha Christie books featuring the aging spinster sleuth.

But forget I said that. This is not the Miss Marple we've become accustomed to, either in the original books or in the marvelous Joan Hickson interpretation (about which, more later) done in the 1980's for PBS.

In no one's imagination (except maybe the film-makers') is Miss Marple anywhere near as rotund, robust, hearty and gruff as she's played by the wonderful Margaret Rutherford, but what the heck, in my view this is Rutherford's movie. Pretend she's not the Miss Marple we all know and/or remember. Just think of her as someone else, a completely different character who happens to be named Marple.

Why, in the movie, she doesn't even live in St. Mary Mead. Who ever heard of such a thing? Obviously it can't be our dithery Miss Marple with the fluffy air and the knitting needles. The only thing this Miss Marple has in common with our Miss Marple is her intelligence and a will of steel.

This Miss Marple even has a male companion, for goodness' sake, A Mr. Stringer. (Played by Rutherford's long- time husband, Stringer Davis.) He's a librarian and as diffident as Miss Marple is demanding and overbearing. To watch the two of them 'disguised' as train workers, searching for clues along the tracks makes for a very entertaining few minutes.

The film (directed by George Pollock) is based on Christie's 1957 book, 4:50 FROM PADDINGTON or WHAT MRS. McGILLICUDDY SAW.

Mrs. McGillicuddy is a friend of Jane Marple's who is returning home after traveling to London to do some shopping. From the window of her compartment she watches helplessly, horrified, as a woman is strangled across the way in a compartment on a closely passing train. Of course no one believes her because no body is found, on the train or elsewhere.

The only one who believes her tale is her close friend, Jane Marple.

In the book, primarily because of frail health, Miss Marple hires the fabulously efficient Lucy Eylesbarrow to find the body she is sure (after doing a bit of logistical investigation herself) lies somewhere on the Crackenthorpe property - the train tracks follow closely the boundary of the huge estate belonging to the family of a biscuit manufacturer. The estate lies somewhere south (I think) of St. Mary Mead - or maybe north.

But in the film, no St. Mary Mead, no Lucy and no McGillicuddy and no several other characters as well.

So, as I said, forget about the original book and just enjoy the film purely based on the robust charms of Oscar winner Margaret Rutherford who was one of filmdom's more idiosyncratic originals. I adore her, but she takes a bit of getting used to.

Okay, so keeping all that in mind, let's move forward.

Miss Marple decides to investigate the murder of the woman on the train even if the police are not interested. She connives to get herself hired as a maid (!?) at the Crackenthorpe estate - in the film, known as the Ackenthorpe Estate. It was the 1950's when large houses were desperate for hired help.

At the house she is greeted with suspicion by the housekeeper played by none other than Joan Hickson who would, years later, play the definitive and Christie approved Miss Marple. How's that for coincidence? Providential, I call it.

A younger Joan Hickson.

Anyway, Jane is also met with suspicion by the mischievous Alexander (Ronnie Raymond), a curiously erudite young boy with the spiffiest upper class accent you'll ever hear. He is a pleasure to listen to and is the second thing I love best in the film. He's like a miniature version of Anthony Andrews sporting his mesmerizing Brideshead voice.

Ronnie Raymond, an Anthony Andrews look-a-like.

Muriel Pavlow as Emma Ackenthorpe

The rest of the staff consists of a sinister gardener and the aforementioned housekeeper who refuses to stay in the house after dark. The gardner hulks around the estate with a snarly German Shepherd at his side.

Besides Emma Ackenthorpe and Alexander, her nephew, the only other occupant of the huge house is old Ackenthorpe himself, a semi-invalid who mostly remains in bed bellowing orders. He is played in his best bellowing attitude by the wonderful James Robertson Justice - the third reason I love this film.

Ackenthorpe's only visitor seems to be Doctor Quimper (Arthur Kennedy) who arrives to give him injections and oversee his health once or twice a week and who, apparently, has his eye on Emma. He drives the sweetest little 50's coupe you've ever seen.

Ah, the good old days when you could keep a doctor on retainer. However, no one in the film seems to notice that Quimper doesn't have an English accent, but I digress.

Once Miss Marple - on the pretense of practising her golf swing - oh, did I forget to mention that she'd arrived at the house with luggage AND golf clubs? Well, she did. So while out and about on the grounds, she spots some run-down buildings and decides one of them, certainly, is a perfect spot to hide a body.. Later that night she goes to investigate and before you can say, there's a dead body in the Egyptian sarcophagus, there's a dead body in the Egyptian sarcophagus.

The cops are called in, of course, and there's Miss Marple with a smirk and a triumphant gleam in her eye. Inspector Craddock (Charles Tingwell) says, "You?!"

She says, "Yes, dotty old me."

When the three Ackenthorpe n'er do well sons and the husband of their deceased sister (Alexander's father) show up to see what's what at the old homestead (the cops want to interview them), two of the brothers meet a grisly end. The Ackenthorpes are being done away with one by one.

In the end, it's Jane who figures out the far-fetched motive and, more importantly, who the killer is, much to the police's chagrin. She then proceeds to use herself as bait to catch the murderer.

Then we get one of the most downright hilarious marriage proposals you will ever see. Hint: it involves Jane Marple. Wait for it.

As I said, don't expect to see the 'real' Miss Marple here, but make a point to see the film anyway. It's quite wonderful in its own singularly sinister (though very amusing) way. The soundtrack by Ron Goodwin is perfection, employing the use of a jaunty harpsichord in lighter moments.

The other three 'Marple' films starring Margaret Rutherford are even more far-fetched than this one, but as long as you don't expect the Christie character, they're okay. Of the four, MURDER SHE SAID remains my favorite.

Go get 'em, Jane.